my thoughts on the metamorphosis by franz kafka

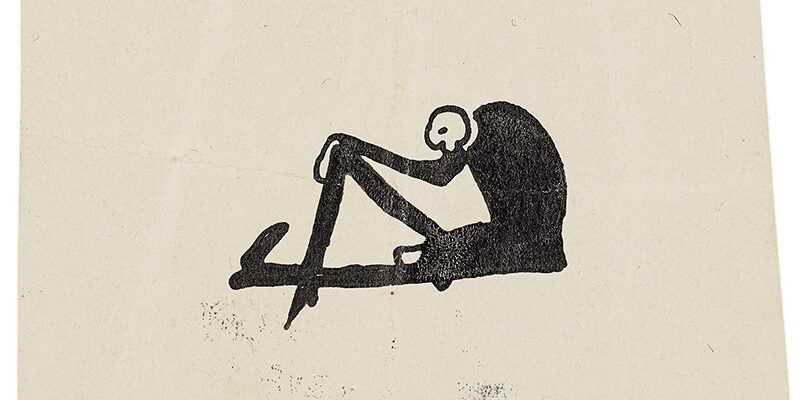

i am but an eggshell that wants to be carried along. but what do i know about being good company? do i really know? all i know about companionship is what i’ve been told. but they barely ever warn you about all the caprice you have to see yourself through. the “little surprises” i bemoan here are not necessarily bad, or unwelcome; they’re even necessary sometimes. rather, i am drawing attention to some of the taciturn roads you have to cross where you could use a little help; some directions, you could say. i know i volunteered to come along and got myself so far, but sometimes i can’t help but feel a little estranged. in love, that is perhaps the root of all my trepidation: the uncertainty of how to love.

actually, i lied. this post isn’t about the metamorphosis. it’s about what i gleaned from reading a critical analysis of it. it turns out, if the author was correct and the story being somewhat autobiographical, then kafka and i share a lot of the same fears, and are surprisingly alike in the our quiet despondence in the face of emotional incapacities.

An interpretation often advanced categorizes Gregor’s metamorphosis as an attempt at escaping his deep-seated conflict between his true self and the untenable situation

What bothers Gregor most about his situation at the company is that there is no human dimension in what he is doing: “All the casual acquaintances never become intimate friends.”

His professional and social considerations are stronger than his desire to quit working for his company. In fact, he even toys with the idea of sleeping and forgetting “all this nonsense.” This “nonsense” refers to his transformation, which he does not want to accept because he sees it only as something interfering with his daily routine. His insect appearance must not be real because it does not suit Gregor the businessman. By ignoring or negating his state, he can, of course, in no way eliminate it. The contrary seems to be the case: the more he wants to ignore it, the more horrible its features become; finally be has to shut his eyes “to keep from seeing his struggling legs.”

He does not really know his innermost self, which is surrounded by an abyss of emptiness. This is why Kafka draws this “innermost self” as something strange and threatening to Gregor’s commercialized existence.

The most terrible insight which the story conveys is that even the most beautiful relationships between individuals are based on delusions. No one knows what he or anybody else really is: Gregor’s parents, for instance, have no idea of their son’s serious conflict, much less of the extent of his sacrifice for them.

As Kafka put it in an aphorism, “It is only our concept of time which permits us to use the term ‘The Last judgment’; in reality, it is a permanent judgment.”

if i knew how to be, i would be better.